Perspectives on a spearing

On 7 September 1790 (two hundred and thirty-two years and one day ago – I am posting this blog on 8 September 2022), on a beach in Manly Cove, the Governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, was speared through the shoulder by a First Nations man. I had written a chapter for my book (‘More Than I Ever Had’) on this event, but as it didn’t make the final version I have uploaded it to my website as an additional chapter. Elizabeth Macarthur (the long suffering wife of John Macarthur), Lieut.-Gov David Collins, Lieut. Watkin Tench and a master’s mate from the Sirius, Mr Southwell, each provided their perspective on the incident in letters and journals. Following, is a compilation of their reports of events leading up to, during and after the incident.

Lieutenant Watkin Tench notes in his journal on 7 September, 1790:

WT “Captain Nepean, of the New South Wales corps, and Mr White[1], accompanied by little Nanbaree[2], and a party of men, went in a boat to Manly Cove, intending to land there, and walk on to Broken Bay. On drawing near the shore, a dead whale, in the most disgusting state of putrefaction, was seen lying on the beach, and at least two hundred Indians surrounding it, broiling the flesh on different fires, and feasting on it with the most extravagant marks of greediness and rapture. As the boat continued to approach, they were observed to fall into confusion and to pick up their spears; on which our people lay upon their oars: and Nanbaree stepping forward, harangued them for some time, assuring them that we were friends. Mr. White now called for Baneelon[3]; who, on hearing his name, came forth, and entered into conversation. He was greatly emaciated, and so far disfigured by a long beard, that our people not without difficulty recognized their old acquaintance. His answering in broken English, and inquiring for the governor, however, soon corrected their doubts. He seemed quite friendly. And soon after Colbee came up, pointing to his leg, to shew that he had freed himself from the fetter which was upon him, when he had escaped from us.

When Baneelon was told that the governor was not far off, he expressed great joy, and declared that he would immediately go in search of him; and if he found him not, would follow him to Sydney. ‘Have you brought any hatchets with you?’ cried he. Unluckily they had not any which they chose to spare; but two or three shirts, some handkerchiefs, knives, and other trifles, were given to them, and seemed to satisfy. Baneelon, willing to instruct his countrymen, tried to put on a shirt, but managed it so awkwardly, that a man of the name of M’Entire, the governor’s gamekeeper, was directed by Mr. White to assist him. This man, who was well known to him, he positively forbade to approach, eyeing him ferociously, and with every mark of horror and resentment. He was in consequence left to himself, and the conversation proceeded as before. The length of his beard seemed to annoy him much, and he expressed eager wishes to be shaved, asking repeatedly for a razor. A pair of scissors was given to him, and he shewed he had not forgotten how to use such an instrument, for he forthwith began to clip his hair with it.

During this time, the women and children, to the number of more than fifty, stood at a distance, and refused all invitations, which could be conveyed by signs and gestures, to approach nearer. ‘Which of them is your old favourite, Bar-an-gar-oo, of whom you used to speak so often?’ — ‘0h,’ said he, ‘she is become the wife of Colbee! but I have got Bul-la Mur-ee Dee-in [two large women] to compensate for her loss.’

September, 1790. It was observed that he had received two wounds, in addition to his former numerous ones, since he had left us; one of them from a spear, which had passed through the fleshy part of his arm; and the other displayed itself in a large scar above his left eye. They were both healed, and probably were acquired in the conflict wherein he had asserted his pretensions to the two ladies.

Nanbaree, all this while, though he continued to interrogate his countrymen, and to interpret on both sides, shewed little desire to return to their society, and stuck very close to his new friends. On being asked the cause of their present meeting, Baneelon pointed to the whale, which stunk immoderately; and Colbee made signals, that it was common among them to eat until the stomach was so overladen as to occasion sickness.

Their demand of hatchets being re-iterated, notwithstanding our refusal; they were asked why they had not brought with them some of their own? They excused themselves by saying, that on an occasion of the present sort, they always left them at home, and cut up the whale with the shell which is affixed to the end of the throwing stick.

Our party now thought it time to proceed on their original expedition, and having taken leave of their sable friends, rowed to some distance, where they landed, and set out for Broken Bay, ordering the coxswain of the boat, in which they had come down, to go immediately and acquaint the governor of all that had passed. When the natives saw that the boat was about to depart, they crowded around her, and brought down, by way of present, three or four great junks of the whale, and put them on board of her; the largest of which, Baneelon expressly requested might be offered, in his name, to the governor.”

Elizabeth Macarthur, recalled what she’d been told:

EM “On the 7th of Septr Captn Nepean, and several other Gentlemen went down the Harbour in a Boat; with an intention of proceeding to Broken Bay to take a view of the Hawkesbury River, in their way they put in at Manly Cove (a place so call’d from the Spirited behaviour of the Natives there at the Governors first landing). At this time, about two Hundred Natives were assembled, feeding on a Whale: that had been driven on Shore, as they discover’d no hostile intentions our party having Arms went up to them. Nanberry was in the Boat, and was desired to enquire for Bannylong[4], and Coleby when behold, both Gentlemen appear’d: and advancing with the utmost confidence ask’d in broken English, for all their old friends at Sydney. They exchanged several Weapons for provisions, and Clothes – and gave some Whale bone as a present for the Governor. Captn Nepean knowing this news would be very pleasing to the Govr. dispatch’d a Messenger to inform him of it, and proceeded on towards Broken Bay – The Govr. lost no time, but as soon as he was acquainted with the above circumstances order’d a Boat and accompanied by Mr Collins (The Judge Advocate) and a Lieut Waterhouse of the Navy; repair’d to Manly Cove, he landed by himself, unarm’d, in order to shew no Violence was intended.”

In David Collins’ account:

DC “Anxious to see him again, the Governor, after taking some arms from the party at the Look-out (which he thought the more requisite in this visit, as he heard that the cove was full of natives), went down and landed at the place where the whale was lying. There he not only saw Bennillong[5], but Cole-be also, who had made his escape from the Governor’s house a few days after his capture. At first his Excellency trusted himself alone with these people ; but the few months that Bennillong had been away had so altered his person, that the Governor, until joined by his companions[6], did not perfectly recoiled his old acquaintance. This native had been always much attached to Captain Collins, one of the gentlemen then with the Governor, and testified with much warmth his satisfaction at seeing him again. Several articles of wearing apparel were given to him and his companions (taken for that purpose from the people in the boat, but who, all but one man, remained on their oars to be ready in case of any accident) ; and a promise was exacted from his Excellency by Bennillong to return in two days with more, and also with some hatchets or tomahawks.”

EM “Bannylong approach’d, and shook hands with the Govr. – but Coleby had before left the Spot, no reason was ask’d why Bannylong had left[7] as he appear’d very happy, and thankful for what was given him; requesting a hatchet and some other things which the Govr. promised to bring him the next day, Mr. Collins, and Mr Waterhouse, now join’d them; and several Natives also came forward, they continued to converse with much seeming friendship untill they had insensibly wander’d some distance from the Boat and very imprudently none of the Gentlemen had the precaution to take a gun in their hand, This the Govr perceiving, deem’d it provident to retreat; and after assuring Bannylong that he would remember his promise; told him, he was going.”

WT “They[8] discoursed for some time, Baneelon expressing pleasure to see his old acquaintance, and inquiring by name for every person whom he could recollect at Sydney; and among others for a French cook, one of the governor’s servants, whom he had constantly made the butt of his ridicule, by mimicking his voice, gait, and other peculiarities, all of which he again went through with his wonted exactness and drollery. He asked also particularly for a lady from whom he had once ventured to snatch a kiss; and on being told that she was well, by way of proving that the token was fresh in his remembrance, he kissed lieutenant Waterhouse, and laughed aloud. On his wounds being noticed, he coldly said, that he had received them at Botany Bay, but went no farther into their history.

Hatchets still continued to be called for with redoubled eagerness, which rather suprized us, as formerly they had always been accepted with indifference. But Baneelon had probably demonstrated to them their superiority over those of their own manufacturing. To appease their importunity, the governor gave them a knife, some bread, pork, and other articles; and promised that in two days he would return hither, and bring with him hatchets to be distributed among them, which appeared to diffuse general satisfaction.

Baneelon’s love of wine has been mentioned; and the governor, to try whether it still subsisted, uncorked a bottle, and poured out a glass of it, which the other drank off with his former marks of relish and good humour, giving for a toast, as he had been taught, “the King.”

Our party now advanced from the beach; but perceiving many of the Indians filing off to the right and left, so as in some measure to surround them, they retreated gently to their old situation, which produced neither alarm or offence; the others by degrees also resumed their former position. A very fine barbed spear of uncommon size being seen by the governor, he asked for it. But Baneelon, instead of complying with the request, took it away, and laid it at some distance, and brought back a throwing-stick, which he presented to his excellency.”

EM “…at that moment an old looking Man advanced, whom Bannylong said was his friend, and wish’d the Govr. to take notice of him, at this he approach’d the old Man, with his hand extended…”

WT “Matters had proceeded in this friendly train for more than half an hour, when a native, with a spear in his hand, came forward, and stopped at the distance of between twenty and thirty yards from the place where the governor, Mr. Collins, lieutenant Waterhouse, and a seaman stood. His excellency held out his hand, and called to him, advancing towards him at the same time, Mr. Collins following close behind. He appeared to be a man of middle age, short of stature, sturdy, and well set, seemingly a stranger, and but little acquainted with Baneelon and Colbee. The nearer, the governor approached, the greater became the terror and agitation of the Indian…”

EM “when on a Sudden the Savage started back and snatch’d up a spear from the ground, and poiz’d it to throw the Govr seeing the danger told him in their Tongue that it was bad; and still advanced: when with a Mixture of horror, and intrepidity, the Native discharg’d the Spear with all his force at the Govr, it enter’d above his Collar bone, and came out at his back nine inches from the entrance; taking an Oblique direction…”

DC “..but Bennillong, who had presented to him several natives by name, pointed out one, whom the Governor, thinking to take particular notice of, stepped forward to meet, holding out both his hands towards him; The savage not understanding this civility, and perhaps thinking that he was going to seize him as a prisoner, lifted a spear from the grass with his foot, and, fixing it on his throwing-flick, in an instant darted it at the Governor. The spear entered a little above the collar-bone, and had been discharged with such force that the barb of it came through on the other side.”

EM “the Natives from the Rocks now pour’d in their Spears in abundance; so that it was with the utmost difficulty, and the greatest good fortune: that no other hurt was rec’d in getting the Govr into the Boat.”

WT “Instant confusion on both sides took place; Baneelon and Colbee disappeared; and several spears were thrown from different quarters, though without effect. Our party retreated as fast as they could, calling to those who were left in the boat, to hasten up with fire- arms. A situation more distressing than that of the governor, during the time that this lasted, cannot readily be conceived:-the pole of the spear, not less than ten feet in length, sticking out before him, and impeding his flight, the butt frequently striking the ground, and lacerating the wound. In vain did Mr. Waterhouse try to break it; and the barb, which appeared on the other side, forbade extraction, until that could be performed. At length it was broken, and his excellency reached the boat, by which time the seamen with the musquets had got up, and were endeavouring to fire them, but one only would go off, and there is no room to believe that it was attended with any execution.”

EM “As soon as they return’d to this place[9], you may believe an universal solicitude prevail’d as the danger of the Wound could by no means be asertain’d, untill the spear was extracted and this was not done before his Excellency had caus’d some papers to be arranged – lest the consequence might prove fatal, which happily it did not, for in drawing out the spear, it was found that as no vital part had been touch’d. the Governour having a good habit of Bodily health – the wound perfectly heal’d in the course of a few weeks.”

WT (Regarding the party that had gone on to Broken Bay) “On reaching Manly Cove, three Indians were observed standing on a rock, with whom they entered into conversation. The Indians informed them, that the man who had wounded the governor, belonged to a tribe residing at Broken Bay, and they seemed highly to condemn what he had done. Our gentlemen asked them for a spear, which they immediately gave. The boat’s crew said that Baneelon and Colbee had just departed, after a friendly intercourse: like the others, they had pretended highly to disapprove the conduct of the man who had thrown the spear, vowing to execute vengeance upon him.

From this time, until the 14th, no communication passed between the natives and us. On that day, the chaplain and lieutenant Dawes, having Abaroo with them in a boat, learned from two Indians that Wil-ee-ma-rin was the name of the person who had wounded the governor. These two people inquired kindly how his excellency did, and seemed pleased to hear that he was likely to recover. They said that they were inhabitants of Rose Hill, and expressed great dissatisfaction at the number of white men who had settled in their former territories. In consequence of which declaration, the detachment at that post was reinforced on the following day.”

And, finally, an extract of a letter to home from a youngster named Southwell, a master’s mate on the Sirius:

“I cannot sufficiently express my approbation of your good sense in forbidding those who perused it to publish my insignificant narrative; or my chagrin at their improper conduct who have, notwithstanding, taken the liberty to do so. I saw it, being the concluding part, in the Hampshire Chronicle and Portsmouth and Chichester Journal, Sept’r 7, 1789. Mr Morgan, since we were at sea, came across it, and from peculiarity of stile immediately recognized it, as did most of our principals on board. I add that I am vexed at it for several reasons, and pray you to take care who you honour with a sight of my cobweb productions, if this is the way they honour them. Apropos, that date is the anniversary of the Governor’s misfortune of the year 1790, when he was speared by a native in Manly Bay, in a manner which savours much of imprudence next to folly. Bennilong, as I said in my letters, had made his escape, and this was the first interview since that incident. It, however very near fatal, proved by no means so, as he soon recovered, and it was followed by the fullest intercourse with these people, insomuch that they eat, drink and sleep in the camp with the most perfect sangfroid; and some of their dames, like too many of ours, gladly forego that dear pleasure of nursing their own bratts, and leave them in perfect security to the care of several of the convict women, who are suitably rewarded by the Governor.”

**

Historians have conjectured whether the governor was lured to Manly Cove for the very purpose of spearing him, as a payback for his capture and detention of Benelong and Colebee: the governor had to ‘pay’ for this injustice in order for the First Nations people to forgive him. But then again, it could just have been a case that the person who speared the governor was alarmed from the governor’s actions.

From Watkin Tench: “…the nearer, the governor approached, the greater became the terror and agitation of the Indian. To remove his fear, governor Phillip threw down a dirk, which he wore at his side. The other, alarmed at the rattle of the dirk, and probably misconstruing the action, instantly fixed his lance in his throwing-stick.”

In any respect, relations with Benelong and other First Nations people became cordial again following the spearing.

**

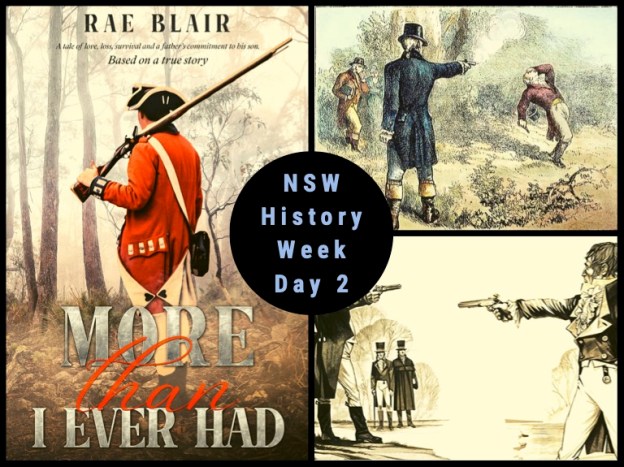

‘More Than I Ever Had’ is based on the true story of Theophilus Feutrill who enlisted in the NSW Corps in 1789 in Birmingham. The book is available from independent booksellers in Sydney and from Amazon.

[1] Surgeon John White

[2] Nanbree or Nanbarry, nephew of the Cadigal leader Colebee, was brought into the Sydney settlement in April 1789, seriously ill from smallpox, which had killed his mother and father. He recovered after treatment by Surgeon John White, who adopted him.

[3] Also known as Benelong

[4] Also known as Benelong

[5] Also known as Benelong

[6] The governor was accompanied by David Collins and Lieutenant Waterhouse.

[7] Assume Mrs Macarthur is referring to why Benelong and Colebee escaped from their capture by the governor.

[8] Governor Phillip, Benelong and Colebee

[9] Back to the governor’s home