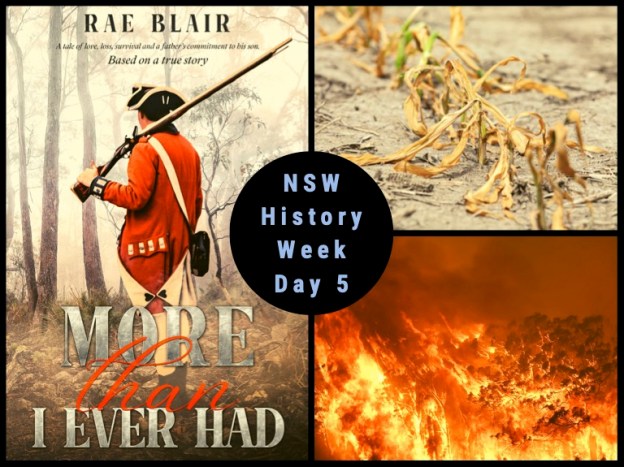

This is my last post for NSW History Week 2022. In this post, I focus on Australia’s harsh environment that the European settlers were faced with. Today, we battle bushfires with modern technology. Back, more than two hundred and thirty years ago, fires were fought with hessian sacks and branches from trees and shrubs. What a challenging world they found themselves in.

A land of drought and fire

How could early European settlers foresee how challenging it would be to grow crops and ensure the survival of livestock in the new penal colony—especially using techniques employed in the northern hemisphere. How would they know how difficult it would be to even live in this country? The settlers of New South Wales battled with flooding rains, drought, humidity and scorching heat, as well as fires started either by lightning strikes or from hunting or land management practices of First Nations people.

Lieutenant Watkin Tench in his journal makes mention of the practices of setting fire to the grass: “The country, I am of opinion, would abound with birds, did not the natives, by perpetually setting fire to the grass and bushes, destroy the greater part of the nests; a cause which also contributes to render small quadrupeds scarce: they are besides ravenously fond of eggs, and eat them wherever they find them. — They call the roe of a fish and a bird’s egg by one name.”

And

“When the Indians in their hunting parties set fire to the surrounding country (which is a very common custom) the squirrels, opossums, and other animals, who live in trees, flee for refuge into…holes, whence they are easily dislodged and taken.”

The effect of heat and fire on the country and its inhabitants is well recorded by Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins, Lieutenant Watkin Tench and Mrs Elizabeth Macarthur.

Fire threatened the settlement of Sydney Cove in December 1792 as Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins noted: “The weather during December had been extremely hot. On the 5th the wind blew strong from the northward of west ; and, to add to the intense heat of the atmosphere, the country was everywhere on fire. At Sydney, the grass at the back of the hill on the west side of the cove, having either caught or been set on fire by the natives, the flames, aided by the wind which at that time blew violently, spread and raged with incredible fury. One house was burnt down ; several gardens with their fences were destroyed, and the whole face of the hill was on fire, threatening every thatched hut with destruction.

The conflagration was, with much difficulty (notwithstanding the exertions of the military) got under, after some time, and prevented from doing any further mischief. At different times during this uncomfortable day distant thunder was heard, the air darkened, and some few drops of rain fell. The apparent danger from the fires, drew all persons out of their houses and on going into the parching air, it was scarcely possible to breathe, the heat was insupportable; and vegetation seemed to suffer much, the leaves of many culinary plants being reduced to powder. The thermometer in the shade rose above one hundred degrees. Some rain falling toward evening, this excessive heat abated.

At Parramatta, and Toongabbe, also, the heat was extreme ; the country there too was every where in flames. One settler was a great sufferer. The fire had spread to his farm; but, by the efforts of his people and neighbours was got under, and its progress supposed to be essentially checked, when an unlucky spark from a tree, which had been on fire to the top most branch, flying upon the thatch of the hut where his people lived, it blazed out, and the hut, with all the out-buildings, and thirty bushels of wheat just got into a stack were in a few minutes destroyed : the erecting of the hut and out-houses (were made) a short time before. We are prepared for the smile which will follow the detail of this loss; a house,with out-houses which cost fifteen pounds, and thirty bushels of wheat to be deemed of sufficient consequence to find a place in the history of a country. Recollect, however, gentle reader, that country was not Great Britain; it was the infant, the distressed settlement of Port Jackson; and circumstances are great or small only by comparison. The man who lost his few pounds, his little all in New South Wales, deplored it as much as he who in a happier land had lost his thousands. This poor man was made a beggar by his calamity; and the man of wealth could not have suffered more.”

Used to the temperate climate of Great Britain, the colonists were in for a rude shock at the intensity of the sun blazing in the new country—blighting their efforts at using timber:

“The timber that had been cut down proved in general very unfit for the purpose of building, the trees being for the most part decayed ; and when cut down they were immediately warped and split by the heat of the sun.”

And during the summer months of the new country soaring and sustained temperatures rendered the crops to dust. David Collins makes a note of this in March 1791:

“At Rose Hill, the heat on the tenth and eleventh of the month, on which days at Sydney the thermometer flood in the shade at 105º was , so excessive (being much increased by the fire in the adjoining woods), that immense numbers of the large fox bat were seen hanging at the boughs of the trees, and dropping into the water, which, by their stench, was rendered unwholesome. They had been observed for some days before regularly taking their flight in the morning from the north-ward to the southward, and returning in the evening. During the excessive heat many dropped dead while on the wing ; and it was remarkable, that those which were picked up were chiefly males. In several parts of the harbour the ground was covered with different sorts of small birds, some dead, and others gasping for water.

The relief of the detachment at Rose Hill took place on one of those and the officer, having occasion to land in search of water, was compelled to walk several miles before any could be found. Sultry days ; the runs which were known being all dry: in his way to and from the boat, he found a number of birds dropping dead at his feet. The wind was about north-west, and did much injury to the gardens, burning up every thing before it. Those persons whose businesss compelled them to go into the heated air declared, that it was impossible to turn the face for five minutes to the quarter from whence the wind blew.”

In November 1791, David Collins noted the number of hospitalisations from the heat had increased and a convict died of sunstroke:

“The mortality during the month of November had been great, fifty male and four female convicts dying within it. Five hundred sick persons received medicine at the end of that time. The extreme heat of the weather had not only increased the sick lift, but had added one to the number of deaths. On the 4th, a convict attending upon one of the gentlemen, in passing from his house to his kitchen, with-out any covering upon his head, received a coup de soleil which at the time deprived him of Speech and motion, and, in less than four-and-twenty hours, of his life. The thermometer on that day stood at twelve o’clock at 943/4º and the wind was N.W.”

And in December 1792, Collins noted the reduction of working hours due to the heat: “The convicts had more time given to them, for the purpose not only of avoiding the heat of the day, but of making themselves comfortable at home. They were directed to work from five in the morning until nine; rest until four in the afternoon, and then labour until sunset.”

In 1796, the high temperatures made wheat a crop with an uncertain future:

“Cultivation was confined to maize, wheat, potatoes, and other garden-vegetables. The heat of the climate, occasional droughts, and blighting winds, rendered wheat an uncertain crop : The harvests of maize were constant, certain, and plentiful; and two crops were generally procured in twelve months.”

In January 1797:

“The Governor, on reaching Toongabbe, had the mortification of seeing a stack containing eight-hundred bushels of wheat burnt to the ground, and the country round this place every where in flames: unfortunately, much wheat belonging to Government was stacked there. The fire had broke out in the evening ; the wind was high, the night extremely dark, and the flames had mounted to the very tops of the lofty woods that surrounded a field called the Ninety Acres, in which were several stacks of wheat. The appearance was alarming, and the noise occasioned by the high wind, and the crackling of the flames among the trees, contributed to render the scene truly awful.

It became necessary to make every effort to save this field and its contents. The jail-gang, who worked in irons, were called out, and told, that if the wheat was saved by their exertions, their chains should be knocked off. By providing every man with a large bush, to beat off the fire as it approached the grain over the stubble, keeping up this attention during the night, and the wind becoming moderate towards morning, the fire was fortunately kept off; and the promise to the jail-gang was not forfeited.

Although at this season of the year there were days when, from the extreme heat of the atmosphere, the leaves of many culinary plants growing in the gardens were reduced to a powder, yet there was some ground for supposing that this accident had not arisen from either the heat of the weather or the fire in the woods. The grain that was burnt was the property of Government, and the destruction made room for as many bushels as should be destroyed, which must be purchased from the settlers who had wheat to sell. If, however, this was the diabolical work of designing selfish villains, they had art enough to baffle the most minute inquiry.”

And in February 1797:

“Erecting a granary, completing a wind-mill, and repairing the public roads, formed the principal works during January; in which the weather had been most uncomfortably hot, accompanied with some severe thunder storms, during one of which both the flag-staff at the South Head, and that at the entrance of the Cove, on Point Maikelyne, were shivered to pieces by the lightning.

The vast blazes of fire which were seen in every direction, and which were freshened by every blast of wind, added much to the suffocating heat that prevailed.”

And

“The weather was now becoming exceedingly hot ; and as, at that season of the year, the heat of the sun was so intense that every sub-stance became a combustible, and a single spark, if exposed to the air, in a moment became a flame, much evil was to be dreaded from fire. On the east side of the town of Sydney, a fire, the effect of intoxication or carelessness, broke out among the convicts’ houses, when three of them were quickly destroyed ; and three miles from the town another house was burnt by some runaway wretches, who, being displeased with the owner, took this diabolical method of shewing their ill-will.”

In January 1799:

“The wheat proved little better than chaff, and the maize was burnt up in the ground for want of rain. From the establishment of the settlement, so much continued drought and suffocating heat had not been experienced ; the country was in flames, the wind northerly and parching ; and some showers of rain which fell on the 7th were of no advantage, being immediately taken up again by the excessive heat of the sun.

March 1799:

“The great drought and excessive heat had affected the water. Such ponds as still retained any were reduced so very low, that most of them were become brackish, and scarcely drinkable. From this circumstance, it was conjectured, that the earth contained a large portion of salt ; for the ponds even on the high grounds were not fresh. The woods between Sydney and Parramatta were completely on fire, the trees being burnt to the tops ; and every blade of grass was destroyed.”

And the last word comes from Elizabeth Macarthur, in one of her letters dated 7 March 1791

“…in spite of Musick I have not altogether lost sight of my Botanical studies; I have only been precluded from pursuing that study, by the intense heat of the Weather, which has not permitted me to walk much during the Summer, the Months of December, and January, have been hotter than I can describe, indeed insufferably so. The Thermometer rising from an 100 to an 112 degrees is I believe 30 degrees above the hottest day known in England – the general heat is to be borne – but when we are oppressed by the hot winds we have no other resource – but to shut up ourselves in our Houses and to endeavor to the utmost of our power to exclude every breath of air – This Wind blows from the North, and comes as if from a heated oven. Those winds are generally succeeded by a Thunder storm, so severe and awful, that it is impossible for one who has not been a Witness to such a Violent concussion of the Elements to form any notion of it. I am not yet enough used to it, to be quite unmoved, it is so different from the Thunder we have in England. I cannot help being a little Cowardly, yet no injury has ever been suffer’d from it, except a few sheep being kill’d which were laying under a Tree, that was struck by the Lightning, a Thunder storm has always the effect to bring heavy rain, which cools the air very considerably. I have seen very little rain, since my arrival, indeed I do not think we have had a Weeks rain in the whole time: the consequence of which is, our Gardens produce nothing, all is burnt up, indeed the soil must be allow’d to be most wretched and totally unfit for growing any European productions tho’ a stranger would scarcely believe this, as the face of the ground at this moment, where it is in its native state is flourishing even to Luxuriance; producing fine Shrubs, Trees, and Flowers, which by their lively tints, afford a most agreeable Landscape. Beauty I have heard from some of my unletter’d Country Men is but skin deep, I am sure the remark holds good in N: S: Wales.”

European settlers persevered and learnt many lessons in how to live and thrive in the harsh environment that is Australia. Today, we still battle with raging bushfires and devastating drought. Science and technology is more important than ever to enable Australians to grow food and thrive in an increasingly hostile and unreliable environment, but we take some comfort in realising that our environment today is not so very different from that more than two hundred years ago.

**

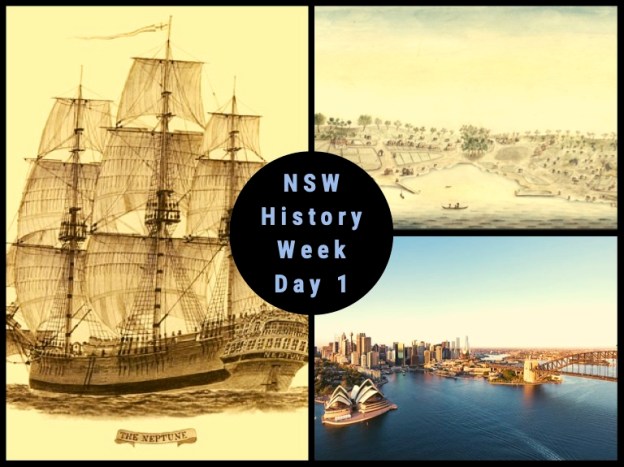

‘More Than I Ever Had’ is based on the true story of Theophilus Feutrill, who came to Sydney Cove in 1790 as part of the Second Fleet as a private in the NSW Corps. The book is available from independent booksellers in Sydney and Amazon.