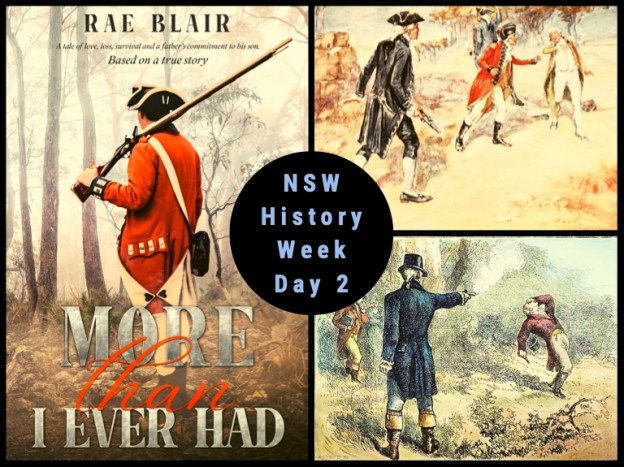

Duelling personalities: Part I

In support of NSW History Week 2022, here is the second of five stories (presented in three parts) that formed the basis of my research for my novel More Than I Ever Had. This book is based on the true story of Theophilus Feutrill, who enlisted in the New South Wales Corps in 1789 in Birmingham.

In eighteenth century England, duelling—that is an arranged shooting between two people for the sake of honour—was against the law, and to kill in the course of a duel was judged as murder. However, it was widely practiced by the male members of ‘nobility’ and the upper classes where one’s honour needed to be restored. The conduct of a duel is at the combatant’s discretion and mutal agreement—they could stand back to back and walk ten paces and turn and shoot; they could start at opposite ends of a clearing and walk towards each other with pistols held in arms outstretched and shoot, or they could stand at a prescribed distance and toss for who gets to shoot first. A constant requirement is that the combatants must have seconds, whose job it is to load the pistols, and confer with each other as representatives of the combatants. A neutral person makes a signal for the duel to commence.

In Bilston, the west-midlands of England, where Theo was raised in the mining and manufacturing community, he would not have witnessed any duels. But he didn’t have to wait long after he boarded the Neptune to watch his first. In fact, the Neptune hadn’t even left English waters before tempers spilled over and someone’s ‘honour’ needed to be restored. And, there were at least two more held in Sydney in the very early days of settlement, one involving the ambitious and fiery John Macarthur (he was also involved in the first one), and one involving Theo’s captain, Captain William Hill.

Duel number one: Macarthur v Gilbert 1789. Tempers on board

Ambitious and newly promoted, Lieutenant John Macarthur boarded the Neptune, with his wife and young son, to sail to New South Wales as part of the NSW Corps. As the ship pulled away from Woolwich Wharf, he, and other members of the military, soon realised they had no status on the ship, being under the complete control of the ship’s captain, Captain Thomas Gilbert, and his crew. And, worse, Captain Gilbert and his crew had little regard for the comfort and welfare of the passengers. Macarthur’s bitter complaints to the captain about the quarters provided to him and his family were disregarded, which led to a blazing confrontation. The Sydney Morning Herald published an article, in February 1945, which recounted the following story:

“The casus belli between Macarthur and John (sic) Gilbert, the captain of the ship, arose from the former’s complaints regarding the location and fittings of his cabin, and ‘the stench of the buckets belonging to the convict women of a’morning.’ Gilbert threatened to write to the War Office and have Macarthur and his wife turned out of the ship. Gilbert gave Macarthur a punch on the breast. Nepean interfered and patched up the quarrel temporarily…..On the seven days trip round to Plymouth there was another flare-up, Macarthur accusing the captain of ungentlemanly conduct towards himself and his wife, and calling him publicly on the quarter-deck—he had a fine capacity for vituperation—‘a great scoundrel’. In retaliation, Gilbert told Macarthur that he had ‘settled many a greater man than him’, and that he was to be seen on shore, whereupon Macarthur named 4 o’clock at the Fountain Tavern, Plymouth Docks. They met, a duel was fought—apparently a bloodless one—honour was satisfied and both parties agreed to live in harmony thereafter.”

Theo and his brother soldiers would have gathered nearby to watch the duel, hoping ‘their’ Macarthur would prevail, but wondering whether they were about to witness someone being shot dead.

Despite Macarthur and Gilbert declaring a truce, the harmony was not to last, with both parties continuing to quarrel. Whilst the ship was laying over at Plymouth, Captain Nicholas Nepean took the opportunity to write to his brother Evan Nepean who was Under Secretary of State in the Home Department, complaining about the ship’s captain. By the time the ship docked at Portsmouth, a replacement for Captain Gilbert was waiting. Whilst the replacement captain was a welcome sight for all on board, he proved to be even more heartless, causing Elizabeth Macarthur to write in her diary that Captain Gilbert was a “perfect sea-monster.” The situation onboard became intolerable for the Macarthur family to the point where they arranged to be transferred mid-ocean to the Scarborough. Theo wasn’t as fortunate.

**

‘More Than I Ever Had’ based on the true story of Theophilus Feutrill is available through independent booksellers in Sydney and from Amazon. Link to Amazon Australia site here.