If this is the first of my posts you are reading, then I suggest you go back to Part I and read the posts in sequence.

Introduction

Up to this point of my family history research, I’d travelled as far as to Perth to uncover information about my 2x Great-grandfather, John Willington Jackson (JWJ). Sitting at my desk interrogating the internet provided the bulk of my research results. Now I knew where JWJ was born and who his parents were, I was keen to delve deeper. We were fortunate to plan a trip to the UK and Ireland in 2017, so I developed an itinerary around searching for my ancestors.

Before we travelled to Ireland, I used information from William Jackson’s Will and his Marriage Record, to ramp up my research. I wanted to know as much as I could about the Jackson and Willington families before we left. See the footnotes for the resources used in my research.

You’ll often hear someone with Irish heritage say, “My ancestors lived in a castle.” So much so, that you’d expect to see castles everywhere in Ireland. Well, there are a lot of castles in Ireland, as we discovered. But some of my Irish ancestors really did live in castles, and to my surprise had influence and wealth.

I hoped to gain a deeper sense of family roots whilst in Ireland, and our visit did not disappoint. A few of the family homes remain standing, and our visit revealed broader family connections. Whilst many records of Irish ancestors have been destroyed, so much remains to be discovered in Ireland. It is a stunning country with a difficult history. My family of Anglo-Irish origin was right in the middle of it all, making Ireland their home for hundreds of years.

Our trip turned out to be a roller-coaster of emotion, a history lesson and one providing deep connection. Some questions remain unanswered, but I learnt things I didn’t expect. I hope you enjoy the following, but drop me a line if you have any questions, or want to provide me with any corrections!

What I learnt about John Willington Jackson’s family before our trip

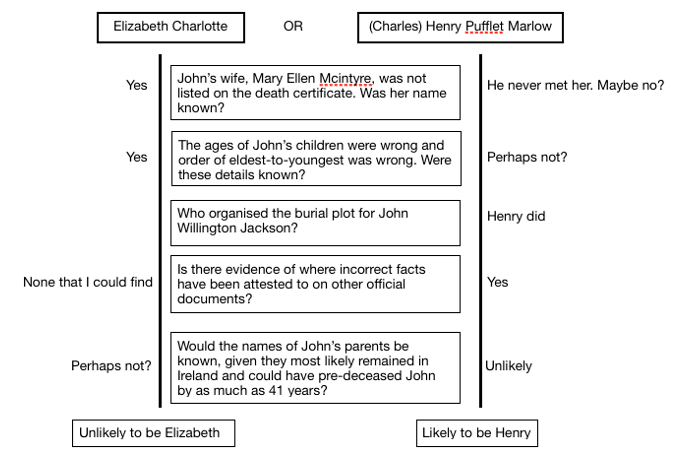

The Jacksons

John Willington Jackson (JWJ), an only child, was born into a lengthy line of landholders and farmers[1]—with significant long-term leaseholds in the premier agricultural area of Tipperary. It is considered that Tipperary is desirable for its superior rich soils and its proximity to Clonmel, the export hub. It attracted the wealthy class of landholders with farms averaging about 50-60 acres, though sometimes, as with the Jackson family, more.

JWJ’s 2x great-grandfather was born in Tipperary (first name unknown—born abt. 1686), but we know at least his great-grandfather George Jackson, farmed a long-term leasehold called Mount Pleasant[2], 448 acres in the northern part of Tipperary near the so-called ‘pan handle’ of County Offaly. Wheat being the dominant crop. George married Anne Minchin, and together they had three sons and two daughters; one son, Minchin Jackson, is JWJ’s grandfather and heir to Mount Pleasant. Minchin had three sons; two of which, George and William, took landholdings nearby (his third son, Minchin, emigrated to Canada with his wife and children)[3]. Eldest son, George, who held the rank of Major in the military, inherited Mount Pleasant upon his father’s death. The Jackson boys all received an excellent English education[4] and most likely were boarders at a school at Usher’s Quay in Dublin.[5]

JWJ’s father William, being the younger son, took two other properties nearby Mount Pleasant during his adulthood: Hermitage[6] and Camira[7].

The home on the property at Mount Pleasant is recorded as being a ‘handsome mansion pleasantly situated’[8], but no longer stands. Whilst Hermitage remains standing today, both homes on the properties Camira[9] and Hermitage[10] were substantial. The Willington family owned all the leaseholds.

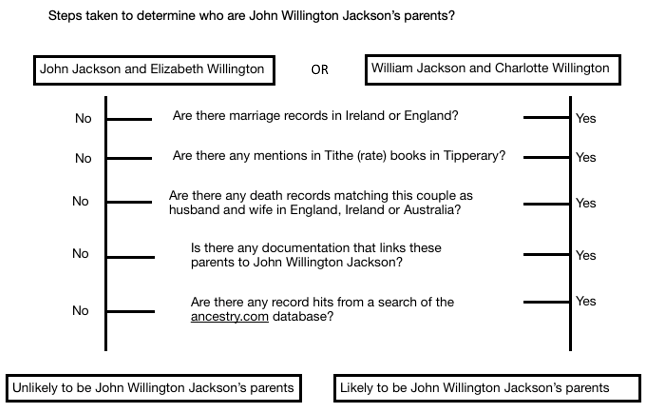

Camira, recorded as the home of William Jackson in the 1850s and at the time of his death in 1867. This image taken circa 1911 (unknown person standing).

Hermitage. William Jackson’s home in 1837[11]. This property stands today.

JWJ’s father, William Jackson, married the landlord’s daughter, Charlotte Willington, in January 1826 at the St Mary’s Church of Ireland in Dublin[12]. Despite living in Tipperary, Charlotte was a member of this Parish Church; William was a member of the local church in Ballymackey[13].

Thirteen members of JWJ’s family are buried at the Ballymackey Church graveyard.[14] The earliest grave is of JWJ’s great-grandfather, who died in 1770, and the most recent is of a cousin buried in 1951. Neither William or Charlotte’s remains are there. Buried in the group are the family members belonging to JWJ’s uncle, George.

John Willington Jackson (JWJ) emigrated to Australia around 1852[15] or 1853. Shipping records show two men called John Jackson aged 23/24 arrived in Australia in 1853. One, of Irish nationality, arrived on the Miles Barton, another via New York (from Canada) arrived on the Scargo. By the time JWJ arrived in Australia, Ireland’s potato crop had just recovered, and over 1 million Irish had emigrated to escape the Great Famine. Tensions continued between Anglo-Irish Protestant landowners and Irish-native Catholic workers and, by 1831, Protestants comprised only 6% of the population in Nenagh (North Tipperary). The small middle-class in North Tipperary had begun to wither away, leaving the area even more polarised. By 1840, the need for the impoverished minor gentry to eject tenants, as they reverted their land to demesne pasture, made Tipperary the second worst county in Ireland for ejections.

Eight hundred Protestant families emigrated from Tipperary to Canada over the period 1818 to 1860, and the largest outflow of Protestant emigrants in a five year period were in the years 1830/34. Catholic emancipation in 1829 had contributed to this. After the mid-1850s, Protestant emigration from North Tipperary to Canada fell, and the direction changed to Australia and New Zealand.[16]

Perhaps JWJ could not see a future for himself in Ireland? His Uncle Minchin’s successful emigration might also have contributed to his decision to leave his homeland. In any respect, JWJ’s crystal ball was working well that day.

The Willingtons

The Willington family owned most of the land in northern Tipperary, including the land leased by the Jackson family[17][18]. They were landlords and farmers and people with significant connections.

JWJ’s mother Charlotte Willington was born to John and Jane (Going) Willington[19] at Castle Willington (around 1800). However, she wasn’t born in the original Castle Willington (although the decayed structure remains on the property. See Appendix I for detail of the original castle). In about 1730, they built another Castle Willington building on the property[20], and it was in this building Charlotte was born.

Charlotte’s father, John, was the third son (sixth child) born to Jonathon and Mary (Drought) Willington in 1755 and was also born at Castle Willington. He inherited the estate after his elder brothers died without issue.

John’s father, Jonathon, was the third son born to James and Mary (Carden) Willington in 1691, and he was born at Killoskehane Castle. The eldest son inherited Killoskehane, the next son, James, gained a property at Newhouse, and Jonathon acquired Castle Willington.

Jonathon’s father, James, was born to John Willington (mother’s name not known yet) around 1646 in Warwickshire, England. By the age of 20, James was living at Killoskehane Castle in Tipperary (a few years after Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland, where land was taken and redistributed.)

The Castle Willington property. The original castle (in the background) (above mage); Castle Willington built in 1730 (below image)

Killoskehane Castle

Killoskehane Castle—the home of the Willington family since ~1666—was built in 1580 by Theobald Walter Butler of Kilkenny’s powerful Butler clan (see Appendix II). The oldest part—a fortified tower block house with six-foot-thick walls—was completed in 1600 and the rest of the building finished around 1730[21]. In the 1800s, Killoskehane Castle was described as being located amongst ‘very fine pasturage’ and with ‘plenty of good limestone.’ The castle itself was situated in ‘a well-planted demesne and includes part of the ancient castle in the modern mansion.’[22]

The Willington family has a family burial plot at the Templemore Old Church in Templemore where 13 members of the family are buried. Another six family members are buried in the front graveyard area of the church, including JWJ’s grandparents, John and Jane Willington[23].

A family tree of the Jackson and Willington families is below:

The Jackson and Willington families (abridged for clarity)

George Jackson b 1706 at Mt Pleasant m Anne Minchin

1. George b 1761 at Mt Pleasant m Eliza?

2. Minchin b 1765 at Mt Pleasant m Mary Anne?

2.1 George b 1786 at Mt Pleasant m Anne Nesbit Anderson, then Letitia Herbert

2.2 William b 1798 at Mt Pleasant m Charlotte Willington

2.2.1 John Willington Jackson b 1829 at Hermitage m Mary Ellen McIntyre

2.3 Minchin b 1810 at Mt Pleasant m Frances Errington

James Willington m unknown

1. James b 1646 in Warwickshire m Mary Carden

1.3. Jonathan b 1691 at Killoskehane Castle m Mary Drought

1.3.6 John b 1755 at Castle Willington m Jane Going

1.3.6.1 Charlotte b abt. 1800 at Castle Willington m William Jackson

1.3.6.1.1 John Willington Jackson b 1829 at Hermitage m Mary Ellen McIntyre

Our trip to Ireland—further discoveries!

In planning our trip to Ireland, I now knew about John Willington Jackson’s family. I plotted out driving distances between the family properties and recorded geographic locations. I’d seen photos of the properties but now wanted to see the locations. I had many questions that I could not resolve through online searching and hoped for further understanding.

Sitting in the plane heading to Ireland, I had no idea that the properties I had already discovered, impressive though they were, were humble compared to what I would uncover during our trip.

After two days in Dublin, and a night in Kilkenny, we arrived in Cashel, Tipperary on 28 July. We spent the rest of the day wandering The Rock of Cashel, which was memorable, and learning some Irish folklore of the area, including about the Devil’s Bit Mountain, which we could see in the distance (so-called because it looks like a bite was taken from it ‘by the Devil’ who flew over the mountain and dropped the bit onto the site where the Rock of Cashel now stands). The Devil’s Bit Mountain looms over land occupied by the Willington and Jackson families.

I had allocated the next day, 29 July, to drive past the family properties and visit the graves of Jackson and Willington family members. I scheduled the day after that for a countryside walk, then checking out on the 31st to leave the Tipperary area.

Killoskehane Castle (Willington)—part I

Like every day we were in Ireland, a light drizzle greeted our morning on the 29th, and it was still raining by the time we reached the bottom of the Devil’s Bit Mountain. Sitting in the car with the windscreen wipers going, we decided against a walk up the mountain, so headed to Killoskehane Castle. The weather had cleared by the time we reached its locked wrought-iron gates. In the distance was a building at the end of a long driveway. Someone cared for the property, but it didn’t appear anyone was there. It frustrated me I could not get closer to my ancestors’ home, or even just wander the grounds. The thought flitted through my mind to jump the low(ish) bluestone wall, but common sense prevailed (that is, my husband talked me out of it) and we remained sensibly on the outside. Getting back into the warmth of our hire car, I dove back onto the internet and searched for any information about the current ownership of Killoskehane. I found the name of the person who had purchased the property in 2015. But how to contact him? Did he still own it? Assuming he was a professional person, I took a chance that he might be on Linked-in, and there appeared a person with the same name. I dashed off a message and hoped it was him and that he would respond. We left Killoskehane with the hope we could return.

Camira, Castle Willington, Hermitage and Mt Pleasant (Jackson)

We then drove about 25 minutes through lush countryside, down narrow roads with high hedgerows either side. Twice we had to stop and back-up to avoid trucks that were pruning the hedges. Bike riders also appeared out of nowhere, speeding towards us around blind bends. Close now to Camira, our car travelled along a stretch of road, perhaps 300 metres where leafy trees on either side of the road grew up and reached over as if to link hands with each other, to create a tunnel through which dappled light decorated the road. Foliage grew thick on both sides of the road and consumed even the power poles.

With a constant check on our GPS, I didn’t realise I was holding my breath until we arrived at a sweeping entrance of old handmade bricks holding two locked rusted gates. All around the gates and beyond nature has reclaimed the land. There is not much to see of Camira with the home gone. An old open shed stood in the distance. Standing in the driveway I imagined William and Charlotte returning home and going through these very gates.

We then headed to Hermitage, which was about a 10 minute drive from Camira. In contrast, the property Hermitage is habitable. The (ubiquitous) locked wrought-iron gates were in good repair, painted black with gold tips, but the Gate House was in original condition and was being subsumed in nature. Beyond, the driveway wound around out of sight—the tall trees which lined the road obscured the building. The satellite view of the property on Google Maps shows the house tucked behind the trees, overlooking the Ollatrim River and surrounded by acres of pasture. As I didn’t find out who owned this property, and as I am not one for arriving at someone’s home unannounced, I didn’t ring the gate buzzer.

Back in the car, a quick drive took us to Castle Willington, also near the Ollatrim River. Again, we stood at locked wrought-iron gates. But this time, we could see the property. Curtains hung in the windows, and the sweeping lawn was bordered with a well-attended garden. We walked around the perimeter of the property to gain a better view of the original castle structure. Ivy had wound its way throughout the remains. I couldn’t find out who the current owners were, so we jumped back in the car and drove to Mount Pleasant.

Mount Pleasant, the seat of the Jackson family, is about a seven-minute drive from Castle Willington, and Hermitage is about the same distance ‘as the crow flies’. A low white painted brick fence borders one edge of the property and a long driveway splits the land. Beyond the vast pasture, the driveway leads to some buildings; but I couldn’t find any records that confirm that the original home remains. Like Hermitage, many acres of farmland surround this property. Standing by the entrance to the property, it occurred to me it might be where the murder of JWJ’s first cousin, John Andrew Jackson, took place in 1863. The murder believed to be part of the violent agrarian movement of the time[24]. John Andrew Jackson had inherited Mount Pleasant from his father (JWJ’s uncle) George who had died the year before.

Jackson family graves

A brief drive took us then to the Ballymackey Church of Ireland, where many Jackson family members are buried. The church, a beautiful structure though derelict, no longer has a roof, and the interior has gone, although some wall plaques remained. It was a surprise to see these wall plaques commemorated five members of the Going family. I recalled the surname, so checked my paperwork to find the Going name mentioned twice. First, Jane Going was Charlotte Willington’s mother, and second that the Rector of Ballymackey was Robert Going[25]—Charlotte Willington’s grandfather (JWJ’s great-grandfather). The plaques commemorated Robert’s son, Thomas, his wife and children. Also, in the front part of the church we found two graves belonging to Willington family members. This church had been an important focal point for my ancestors.

We wandered around the thick grass of the graveyard until we found the group of Jackson graves, with 13 family members commemorated on four headstones. The inscriptions were almost legible, but as a local historical society[26] had transcribed them, I could work out the inscriptions.

At least 13 Jackson family members are here; the oldest being JWJ’s great-grandfather (my 5x great-grandfather) George Jackson (d. 1770), and the most recent being for JWJ’s cousin Mary Jackson (d. 1951). All the Jackson family buried here belong to JWJ’s uncle, George’s family.

It was moving to be standing at the grave of my 5x great-grandfather, George, who died 250 years ago, and to place wildflowers on his grave.

Templemore

The market village of Templemore is a 30 minute drive from Ballymackey, and we headed there to visit the Templemore Old Church, in Templemore Park, to see the burial plot of the Willington family.

The Willington burial plot is on the north side of the ruins of the Templemore Old Church. We had entered Templemore Park at the end furthest away from the church, so we enjoyed a walk amongst the forested park, along meandering paths including a fairy trail, then down the tree-covered promenade past the lake.

The ruins of the old church are just east of the ‘pitch and put’ golf course. On the other side are some open playing fields. We walked through the graves on the south side of the church around to the northern side where we found the Willington burial plot.

Many tombs crowd the plot, and it was disappointing to see them damaged. The plot appears to be an area where young people congregate, as there were a few discarded empty drink cans scattered around. The inscriptions on the tombs were difficult to read. I fussed over one tomb, which had big clumps of dirt on top, trying to clean up the tomb as best I could and to decipher the inscription. I glanced up to see a red-haired gentleman walking towards us with two children in tow holding golf clubs. He asked if we needed help.

We introduced ourselves and said why we were visiting. Upon learning that we were from Sydney, he brightened up. “How about the start of the Sydney Swans season then?!” he said, referring to the Australian AFL team. It transpired that a local Templemore boy had signed up to play with the Sydney Swans but had yet to make it to the first grade. The locals were avid watchers of the Swans’ games to support him. My only disappointment is that of all of my immediate family, I was the last one you want to talk to about AFL. The rest of the family are ‘dyed in the wool’ Sydney Swans fans, which stemmed from the club’s origins being from South Melbourne. When JWJ came to Australia, his family lived in South Melbourne and stayed there for many generations.

The gentleman who came to speak to us was an active member of the local historical society. He suggested we go over to the Templemore Library as “Willie Hayes” had transcribed the tombs and his book was there. But he also told us about the park’s origins, and that it was originally the home of the Carden family. The Carden burial plot was the one next to the Willington one.

My ears pricked up. Mary Carden was JWJ’s 2x great-grandmother, and she married Jonathon Willington. I had not researched her family. Could she be part of this Templemore family? He confirmed that she was.

After he left, we headed over to the Templemore Library for a copy of the Willie Hayes book, but their copy was out.[27]

As soon as we arrived back at our hotel, I dove into researching the Cardens (and continued my research back in Australia). I learnt that Mary’s father was John Carden, whose father came from Cheshire in the wake of the Cromwellian settlement of the 17th century. He purchased land from the Butlers (~2,500 acres) and lived in the Butler Castle in the park (built circa 1450). Renamed Templemore Castle, fire destroyed it around 1740. It was here that Mary was born.

The Templemore Castle ruins, known as the Black Castle, remain. The Cardens then lived in a house called The Priory. About 1856 building works took place on The Priory and renamed to Templemore Abbey. The Cardens laid out the park with its artificial lake and developed a market town around it. Generations later, they abandoned the Abbey when a marriage ended through an act of infidelity by the last head of the Templemore branch of the Cardens. Revolutionary forces destroyed[28] the extensive neo-Gothic mansion during the Irish War of Independence in 1921, and the expansive grounds are now the public Templemore Park.

Templemore Abbey—the Carden family seat from 1698 to 1902. Now that’s some family home!

Killoskehane—part II

By the next day, 30 July, I had heard from the owner of Killoskehane. He regretted that he was out of the country and that perhaps “another time” might be suitable for our visit. It was deflating news. Time was running out for me as we were leaving the area the next day. The owner kindly took my phone calls and after a bit of back and forth, he organised for the groundskeeper to let us to come onto the property.

Rushing back to Killoskehane, we met the groundskeeper who unlocked the gates. As we drove through along the driveway, the castle filled our windscreen before we pulled up at the ‘back’ entrance. The groundskeeper walked us around the property and filled us in on what developments the owners had planned. I felt full of gratitude to see someone spending the funds required to care for my ancestral home. I peered through the front windows into the dining and sitting rooms, through glass warped with age. Bright sunlight broke through the clouds and showed us Killoskehane at her best.

As we walked back around to the cars, the groundskeeper said, “I have a surprise, I’m allowed to let you in.”

Before we knew it, he’d unlocked the door and we stepped inside. He showed us the kitchen, hallways and through to the dining and sitting rooms. As a heritage-listed building, they can change very little about the property, so it was amazing to see original pieces in situ.

It was incredible to be in the space. I stood on the stairs and placed my hand on the handrail, the same handrail JWJ’s 2x great-grandmother (my 6x great-grandmother) had placed her hand. Walking through the hallways, I could hear Oliver Cromwell’s boots echoing on the floorboards, from the time he commandeered the castle during his conquest of Ireland in 1649. The master bedroom also contains a secret escape hatch.

Ornate bedhead in the main bedroom of Killoskehane Castle

Killoskehane Castle interior

It was an unforgettable moment to spend that brief time in Killoskehane Castle, a property that has much significance for the Willington and Carden families, and I am grateful to its owner for his kindness.

In 1855, the Willington family sold part of the Killoskehane estate to the Carden family (who had an adjoining property in Barnane).

In 1862, John James Willington, the then owner of Killoskehane Castle, died unmarried. His brother, Jonathan, who had been an officer in the army, and a resident of the Richmond Lunatic Asylum in County Dublin had also died unmarried in 1870. Killoskehane passed into the hands of their widowed sister, Dublin-based Alicia Willington. Nine years later, John Rutter Carden[29] purchased Killoskehane and spent money on it before selling the entire 1,305 acres to Col. Albert Fytche for £53,000 (but subject to further work being completed by the Carden family).

They sold the property with all of its furniture and fittings (including crockery) intact, and most of these remain in the house today. Today, the current owner makes the property available for hire through AirBnB, in an endeavour to recoup some funds they’ve had to spend on it.

I provide more information on Killoskehane Castle in Appendix III.

St Mary’s Church—Dublin

When we arrived in Dublin, the top-of-the-list thing for us to do was to visit St Mary’s Church—the place where William Jackson married Charlotte Willington. I was curious as to why Charlotte’s family would worship here, rather than at their local church.

The church opened in the late 17th century and was deconsecrated in 1986. It now operates as a bar and restaurant called The Church. We booked in for dinner, but arrived early to look around.

The downstairs floor area is clear of pews etc., and now features a central bar, around which are tables and chairs. Guests can also dine on the first floor mezzanine level (where we sat) which overlooks the ground floor. Stunning stained glass windows illuminate the church, and original memorial plaques adorn the walls. Down one end, opposite the stained glass windows, is the church organ, upon which Handel played his first public performance in Dublin of Messiah.

On the ground level we found a memorial plaque dedicated to the Marquis and Dowager Marchioness of Ormonde and members of their family (the Butler family) who are interred in a vault under the church. A leaflet on the history of the church also informed us of other notable parishioners who attended the church.

It now made sense why the Willington family would be parishioners here. It would have been advantageous for them to worship amongst the wealthy and powerful and it appears to have paid off, at least with the marriage of Bridget Butler in 1785 into the Willington family (her remains are in the Willington burial plot at Templemore).

As we ate our dinner, I looked down to the place where the altar would have been, and imagined JWJ’s mother (my 3x great-grandmother) Charlotte Willington walking down the aisle to marry William Jackson in the middle of winter in 1826. I imagined the guests all dressed up for this ‘society wedding’ and the pride of his father, Minchin, and mother, Mary Anne, that their son was marrying so well, and formalising the connection between the Jackson and Willington families. At least, I hope that was the case.

Charlotte’s father had already died at the time of her marriage, but her 60-year-old mother Jane (Going) Willington would have most likely been there. Charlotte had one older brother living, James (who had inherited Castle Willington), and he might well have been the one to have given her away (he named one of his daughters after her).

William and Charlotte Jackson

Following their marriage they would have lived at Hermitage, the property near to Charlotte’s mother and brother at Castle Willington.

Three years later, they had a son named John Willington Jackson (named after Charlotte’s father).

We know by the 1850s through to 1867 that William lived at Camira, most probably alone and with the help of a servant[30], given that his son had emigrated ~1853.

When William wrote his will in 1867, there is no mention of Charlotte, and his primary beneficiary is his “kind and affectionate sister-in-law Eliza Willington.”[31] It is unknown where Eliza lived during the 1850s.

I have not been able to locate the burial place of William or his father and mother. They are not buried at the local church like William’s grandfather, brother and his brother’s family. Perhaps they are buried at Mount Pleasant?

I also have not been able to find where Charlotte and Eliza are buried, or any records of Charlotte’s death. It is tempting to believe she died in childbirth, given that they only had the one child. Also, given that Camira was Willington-owned land, but leased by the Jackson family, perhaps William and Charlotte are buried together there?

Charlotte’s sister, Eliza, never married, but she was “kind and affectionate” to William, so read into that as you will. William didn’t re-marry. It is possible that Eliza stepped into the mothering role for John, and William had the female company he needed. We can only speculate.

Eliza died on 5 April 1869, two years after William. She was living at Hermitage with her nephew, Robert Willington, who was at the time preparing for his marriage (which took place 15 days later).

Other family lines

The more you learn about a branch of your tree, the more branches make themselves available to you. For example, Charlotte’s mother’s family—the Going family branch—has given me the Maunsell and the Waller family branches. And from these, I find more families. There are many rabbit holes to explore, but for now, I’ve only researched the Going, Maunsell and Waller families. A summary for each follows. For those who are interested, I will populate my ancestry.com family tree with specific details, or contact me for further information.

Going family

JWJ’s grandmother, Jane (Going) Willington, was the daughter of Robert Going, Rector of Ballymackey Church and Margaret (Maunsell) Going. Her grandfather, Robert Going (born at Birdhill Tipperary, 1667) made his will at Rathurles Castle in 1732, which is about 5 kms east of Mount Pleasant, about 25m north of the Ollatrim River and south of Rathurles rath[32] and ancient church. Jane (Going) Willington was born at Traverston[33], the seat of the Going family in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1840, the Ordnance Survey Name Books describe it as “a splendid residence”. Going family members continued to live in the property and the last family member to live in it was Ann Norris (circa 1910). This house no longer exists.

Jane’s uncle, Major Richard Going, was High Sheriff of County Limerick, and murdered[34] in 1821 because of his police activities against the Whiteboys[35]. Several men ambushed him near Rathkeale and shot him from cover of a hedge as he read letters while leading his horse. A neighbour found him still alive, but he died shortly after. His brother, John, was also murdered for his vigoroush attempts to collect his Tithes.[36]

Maunsell family

JWJ’s great-grandmother Margaret Maunsell descended from an ancient and eminent family from the period of the Conquest. We can trace this lineage back to the 16th century with links to the original forebear from the 11th century. A book published in the 19th century contains a piece of ancient local poetry written in the time of Charles I on the Poetical History of the Family of Maunsell, which provides additional information about the family.

Margaret’s father was Thomas Maunsell and the patriarchal line includes many men called Thomas Maunsell up to the 16th century. Many were Barristers-at-Law, as was her father who was also Kings Counsel and Counsel of the Commissioners of Customs. Her mother was Dorothy Waller[37], youngest daughter of Richard Waller, Esq of Castle Waller. Margaret’s grandfather was Richard Maunsell and his second marriage was to Jane Waller[38]—Dorothy’s sister. This made Jane her sister’s mother-in-law!

The first Maunsell to settle in Ireland, Thomas Maunsell, was in 1609[39]. For the family remaining in England, in 1622, John Maunsell gained the manor of Thorpe Malsor, a mile or so due west of Kettering, Northamptonshire. The impressive property continues to be occupied (see Appendix IV).

Waller family

JWJ’s 2x great-grandmother was Dorothy (or Dorothea) Waller. She was the daughter of Richard and Elizabeth (Redmond) Waller of Castle Waller. The Waller family is also one of great antiquity, being a branch of the Warrens of Poynton, co. Chester (circa 1300s). Burke[40] goes into detail about how the family goes from using the surname Warrenne/Warren to Waller. We can trace specific ancestors from early 1600s.

Dorothy Waller’s grandfather, Richard Waller, was a Lieutenant in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649-53), and had not received wages between 31 December 1649 and 13 July 1651. In 1666, when the lands given up by the conquest were redistributed, Richard received Castle Cully, originally owned by the Ryan (originally O’Mulrian) family, which was on the western slopes of Keeper Hill near Newport in southwestern Tipperary County, near Limerick. He also gained a substantial amount of land near the castle and elsewhere, totalling 1,195 acres. Richard Waller was a petitioner to the Council of Agents of the Army in 1655 on behalf of the regiments regarding the conditions of the lands they received in a grant from the government in recompense for service (transcribed in the notes of Dr William Petty in his notes from the Down Survey of 1655-56). These petitions show that Lieutenant Richard Warren Waller was acting on behalf of the English government in Ireland, and that his land was granted for his past and present duties.

Castle Cully was in ruins because of the war and Richard never lived in the castle; he purchased a house in South Ward near the present St John’s Square in Limerick City, using funds from his inheritance. Richard rebuilt Cully using stones from the original castle and renamed it Castle ‘Waller’. According to the 1860 Ordnance Survey letters of Co. Tipperary, its original walls were 38 by 32 and a half feet, six feet four inches thick, and fifty feet long. Richard’s son, Richard (Dorothy’s father), lived in the castle.

Dorothy’s brother William inherited the castle which then went to his eldest son Richard Waller. He married Elizabeth (daughter of Admiral Holland), and the castle passed to their second-eldest son, Richard, who married Anne, daughter of Kilner Brazier. The Castle Waller estate of William Henry Brazier Waller (who emigrated to America) assigned to William De Rythre was advertised for sale in June 1851 (during the famine). The Freeman’s Journal reported that Henry Hodson and John H. Going were among the purchasers.

From the records, Castle Waller was the seat of the Waller family in the 18th and first half of the 19th century, occupied by Richard Waller in 1814 and in 1837. In 1840 the Ordnance Survey Name Books reported that it was then uninhabited. Thomas Mullowney was the occupant at the time of Griffith’s Valuation when the buildings were valued at £17. The owners occupied Castle Waller for some time in the 1850s by William de Rythre who married Blanche Waller–the last of the Wallers to occupy the building. In the 1870s, Michael Moloney of Castle Waller owned 5 acres. The building was in ruins by the early 20th century, and the remains of the original Ryan stronghold (now Castle Waller) still stand.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX I

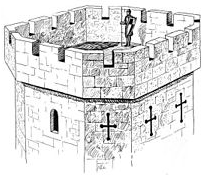

Description of the interior of the original Castle Willington

The original Castle Willington was a tower house[41] design of four storeys, but in the early 17th century the owners inserted an extra floor above the third floor hall. The remnants of the building stands to full height, and although the crenellations are fragmentary, many of the roof weepers[42] are visible. Ivy covers part of the castle and obscures much of the fenestration (the arrangement of windows).

A tower parapet with crenellation.

The pointed doorway in the west wall leads to a lobby, protected by a murder-hole[43]. To the south is a guardroom, and to the north is another lobby. From this inner lobby a pointed doorway leads to the ground floor room. A second pointed doorway from the lobby leads to the spiral stairway in the NW corner. The castle is vaulted above the second floor. At the second floor there is a two-light window in the east wall and single-light windows in the south and west walls. A doorway at the south side of the window embrasure[44] leads to a mural chamber[45].

There are many original floor beams at this level. There are round bartizans[46] at the NE and SW corners and a machicolation[47] in the west wall protects the doorway.

The castle was known as Killowney until the early 18th century, until the landlord, Wellington, built a house just to the SW. This became known as Castlewellington, later changed to Castle Willington, the name now applied to all the buildings on the site. This house, built circa 1730, is a three-storey three-bay structure. About 100 years after its construction, a projecting three-storey single-bay block was added at the west end. This is built in the tower-house style with crenellations, crenellated tourelles[48] at the corners and square hood-moulds over the windows.

APPENDIX II

The Butler family

The Butler family were landowners and for several centuries prominent administrators of Ireland. They were descendants of Anglo-Norman lords who took part in the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th Century. The family took the surname from the hereditary office of Butler of Ireland. Theobald Walter (d. 1205) held the ceremonial cup-bearer or butler position to Prince John, Lord of Ireland (during Henry II’s reign).

The Butler seat since 1391 was Kilkenny Castle and produced Earls, Marquesses and Dukes of Ormonde. The patrimony of the Butlers of Ormonde encompassed most of the modern counties of Tipperary, Kilkenny and parts of County Carlow.

The Butler family was the most influential family in Ireland.

APPENDIX III

History of Killoskehane Castle

Theobald Walter Butler (of the Butlers of Ormonde) built the castle in 1580. Like Nenagh Castle, it was part of the complex group of castles built by the Butlers, whose seat was in Kilkenny Castle. Killoskehane was of sufficient importance to attract Cromwell, who captured the castle for his own use. His escape tunnel is still visible in the bedroom he used.

During some 400 years of history, there have been many illustrious owners. Among them are the Willingtons, whose daughter married Canada’s Irish Governor-General. Later, Edward Downes-Martin owned it, and restored the castle in 1865. He is credited with the stables and the Victorian gatehouse. The infamous Sir John Carden bought Killoskehane during a sojourn in prison “for the abduction of Miss Arbuthnot of Clonmel”. During the next 100 years it fell in quiet disuse. When the Browne family bought it in 1977, they inhabited the castle only on rare occasions during the last 35 years. The Browne family took an enormous effort to restore the building. The roof and chimney stacks had suffered from neglect and needed a total rebuild. Plumbing, heating and electricity were not existent, so the house underwent restoration and renovation works to get it up-to-standard in the late 70s of the 20th century. The Browne family moved from London to Killoskehane Castle and started a whole new chapter of their lives in Ireland. They also completed six bedrooms and made them available to private guests, including a Mr and Mrs Broomall during the 1980s. During a stay with another American couple, the Broomalls and the couple bought Killoskehane Castle as a vacation home for the two families. After a few years the other couple backed out, but the Broomalls kept the place for about 30 years. They spent weeks of great summer vacations in the castle with their children.

In 2015, René Mogge bought Killoskehane Castle after a lengthy search for a period house in Belgium, France, Germany and Ireland. He fell in love with the castle the moment he went up the long driveway for the first time. He took it over a few months later. René and his partner Stephanie have been restoring the place step by step with the help of a great local craftsmen team since then. Five bedrooms and the principal areas have ben finished. More work on additional bedrooms, the original chapel and the lovely porter’s lodge at the entrance of the estate are to be undertaken.

APPENDIX IV

The Maunsell family home

Thorpe Malsor Hall c.1900

In 1622 John Maunsell acquired the manor of Thorpe Malsor, a mile or so due west of Kettering, Northamptonshire. The Jacobean manor house was ‘a development of the medieval H-plan with a central hall and two cross-wings.’[49] The home today looks very much as it did in the 17th century and in 2012 remained in the hands of Maunsell descendants.

The house and All Saints church compose a quintessential scene of parochial authority south of the lane which swings down into and up out of the tiny village of Thorpe Malsor. Unlike their aspirant neighbours on the other side of town, the Maunsells keep the classic profile of the ‘lesser gentry’ with a pedigree dotted with the respected professions (and an estate agent), the odd MP and serial inter-marriage with a few Northamptonshire families of similar standing.

The single significant ‘modernisation’ of the old manor has been that plain ashlar[50] south face. Dated 1817, this major modification happened during the shortest of all the Maunsell tenures, that of William, Archdeacon of Kildare (1815-18), who was sandwiched between two of the longest, Thomas Cecil (60+ years in residence) and Thomas Philip (48 yrs).

‘At the same time the interior was modernised, and there are very few remains of ancient work left inside,‘ noted one 1930s visitor.[51] ‘But the house is full of old objects…many portraits by painters of renown some of which, with other things, came from Rushton, for the Maunsells intermarried with the Cokaynes of Rushton Hall more than once.’

The unbroken run of male Maunsell heirs to the estate ended with the sudden death of Major Cecil John Cokayne Maunsell in 1948. The female line has since predominated and the Hall is home to the Holborows, the Major’s great-granddaughter and her husband (who ironically for a property last on the market in 1622 worked for premier estate agent Savills heading up the country house sales department)[52].

[1] History of the County of Middlesex, Canada (1889)

[2] http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/property-show.jsp?id=4387

[3] Op. cit.

[4] Op. cit.

[5] Marriage record of William & Charlotte; and https://www.knockunion.ie/news/st-vincents-college-ushers-quay-359

[6] A topographical dictionary of Ireland: Comprising the several counties, cities, boroughs, corporate, market and post towns, parishes and villages, with historical and statistical descriptions…, Volume 1. S. Lewis (1840).

[7] Will of William Jackson.

[8] https://www.libraryireland.com/topog/B/Ballymackey-Upper-Ormond-Tipperary.php

[9] http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/property-show.jsp?id=4385

[10] http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/property-show.jsp?id=4386

[11] https://www.libraryireland.com/topog/B/Ballymackey-Upper-Ormond-Tipperary.php

[12] https://churchrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/display-pdf.jsp?pdfName=d-277-3-2-001

[13] Marriage record of William and Charlotte

[14] Gravestone inscriptions County Tipperary. Section B: Barony of Upper Ormond, Volume 8, Parish of Ballymackey (1984) The Ormond Historical Society (Denise Foukes).

[15] According to JWJ’s unreliable death certificate, he arrived in Australia in 1852.

[16] Irish migrants in the Canadas: a new approach. Elliott B.S. (2004)

[17] http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/estate-show.jsp?id=3436

[18]http://titheapplotmentbooks.nationalarchives.ie/search/tab/results.jsp?surname=willington&firstname=&county=Tipperary&townland=&parish=&search=Search&sort=&pageSize=&pager.offset=0

[19] Many facts relating to the Willington family came from Genealogical & Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland (Sir Bernard Burke, 1879)

[20] http://irishantiquities.bravehost.com/tipperary/killowney/willington.html

[21] Lord of the Castle Irish, The Washington Post. Judie Burke Bredemeier. 19 December 1982.

[22] A topographical dictionary of Ireland…(S. Lewis) op.cit.

[23] The Old Church and Graveyard, Templemore in 1995. Hayes, William J.

[24] Between 1850 and 1870, Irish landlords extracted £340 million in rent—far exceeding tax receipts for the same period—of which only 4–5% was reinvested. This led tenants to regard landlords as non-productive parasites, even if they resided on their estate. Conflict between landlords and tenants arose from opposing viewpoints on such issues as land consolidation, security of tenure, transition from tillage to grazing, and the role of the market. The mutual animosity was exacerbated by religious and ethnic differences; the Irish nationalist politician Isaac Butt claimed that the fact that Catholic Irish were tenants to those they regarded as foreigners was worse than “the heaviest yoke of feudal servitude”.

[25] William Jackson Will (1867)

[26] Gravestone inscriptions, County Tipperary, Section B: Barony of Upper Ormond, Volume 8. Parish of Ballymackey. Denise Foukes, The Ormond Historical Society (1984).

[27] The librarian of Templemore Library very kindly photocopied the relevant pages from The Old Church and Graveyard, Templemore in 1995. William J. Hayes, and forwarded these to me by email after we returned home.

[28] Cardens of Templemore, Carden, Arthur E. (2017)

[29] The lease was transferred to John Rutter Carden (“the Woodcock”) while he was incarcerated in Clonmel Goal, part way through his sentence for the attempted abduction of Eleanor Arbuthnot.

[30] William Jackson Will (1867)

[31] Op. cit.

[32] A rath is a strong circular earthen wall forming an enclosure and serving as a fort and residence for a tribal chief. The location of the castle via http://www.thestandingstone.ie/2010/02/rathurles-tower-house-co-tipperary.html

[33] In 1786 it was referred to as ‘Trevor’s-town’

[34] Begley’s Diocese of Limerick (1938).

[35] The Whiteboys were a secret Irish agrarian organisation which used violent tactics to defend tenant farmer land rights for subsistence farming. Their name derives from the white smocks the members wore in their nightly raids.

[36] Rosemary ffolliott’s BMD’s on microfiche in Limerick County Library. (1750 to 1825 approx.)

[37] Burke op. cit.

[38] Burke op. cit.

[39] The Plantation of Ireland process began during the reign of Henry VIII and continued under Mary I and Elizabeth I. It was accelerated under James I (when the Plantation of Ulster took place on land handed over from those Gaelic chiefs who broke the terms of surrender and regrant), Charles I, and Oliver Cromwell.

[40] Op. cit.

[41] A tower house was all about defence and thus many of the features you will find inside have much to do with an expectation of attack and little to do with comfort. When the weapons of attack consisted of bows and arrows, swords and spears, and even muskets, the castle design worked. But as soon as cannon appeared on the scene the tower house was doomed – even its thick stone walls were no proof against such a bombardment.

[42] Holes for carrying off rain water from the wall-walk.

[43] Openings in the roofs of passageways through which missiles and liquids could be dropped onto attackers.

[44] Splayed opening in a wall or parapet. Arrow loops in the merlons (the ‘teeth’ of battlements, between the crenels or embrasures. High sections of battlements)

[45] Mural chambers are spaces within the walls and may have served a variety of purposes from storage to dressing.

[46] Overhanging corner turret. Small turret.

[47] Openings in floor of projecting parapet or platform along wall or above archway, through which defenders could drop or shoot missiles vertically on attackers below. Murder holes.

[48] Type of turret.

[49] Heward, John and Taylor, Robert. The country houses of Northamptonshire. RCHM, 1996

[50] Finely dressed (cut, worked) stone.

[51] Gotch, J.A. Squires’ homes and other old buildings of Northamptonshire. Batsford, 1939.

[52] https://handedon.wordpress.com/2012/03/26/thorpe-malsor-hall-northamptonshire/