Have you finished More Than I Ever Had and want more? Or have yet to read the story? Here’s an additional scene that I couldn’t fit into the book. Enjoy!

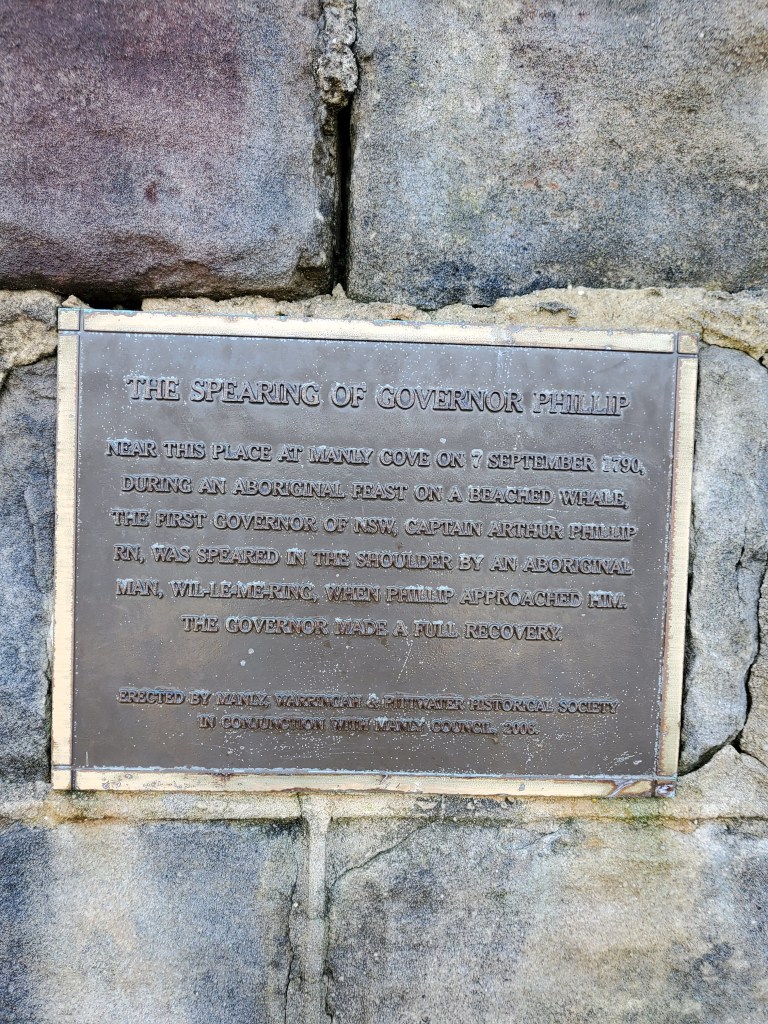

The spearing of Governor Phillip

Port Jackson, September 1790 (three months after landing)

The strangeness of this new land was becoming more familiar as the days passed. Duty devoured Theo’s daylight hours, and night time meant supper, socialising and sleeping. Since leaving the tent hospital, his body grew stronger, responding to long treks in the woodlands to supervise land clearing and planting, breathing fresh, cool air under endlessly high skies. The cold months—mild in comparison to home—seemed to be passing.

The sun had not long risen when Theo made his way to Captain William Hill’s tent. He’d received a summons last night, which was unusual. Normally, Theo’d report to the registrar for his daily duty, or his sergeant, who’d give specific orders. He wondered why the captain wanted to see him?

Theo paused outside the open flap of the captain’s tent. Captain Hill sat behind his desk, finishing signing a document before glancing up at Theo. A mug of steaming tea sat within hand’s reach. The captain noticed Theo and was about to speak when another private appeared by Theo’s side—a short, dark-haired soldier with narrow-set eyes and aged in his late twenties—someone Theo had not yet met.

“Franks, Feutrill, please come in,” Hill said.

The captain folded his hands over the paperwork as the privates entered the tent and assembled before him. “Governor Phillip is heading to Manly Cove this morning to meet with the native called Bennelong and some of his tribe. It is crucial this meeting go well. I’ve selected you both to assist the governor.” The captain sipped his tea. “See the storemaster now, as the governor will take some supplies with him. Get these onto the boat. Also ask the convict overseer to select six men to row the governor and his party—you’ll both be responsible for them. The governor wants to leave in two hours. Is anything unclear?”

“No sir,” Theo responded. Franks shook his head.

“Good, you are dismissed.”

After they’d seen the convict overseer, they headed to the store house. There, Theo signed with his mark for several hatchets, some bread, salt pork and wine. Franks swept up the food and left the heavier bundle for Theo to carry. On their way to the boat, Franks broke off a piece of bread and put it in his pocket.

“Is there a problem?” Franks said, when Theo threw him a look. “You gotta look out for yourself here, mate.”

Theo ground his teeth and adjusted the weight of the supplies he was carrying. This wasn’t a good start. “Let’s just make sure we do our job.” Theo strode ahead. This was the first opportunity Captain Hill had given Theo, and he wanted to make sure the captain would not be disappointed.

Down at the wharf, Theo stepped into the rowboat, balancing himself to receive the supplies from Franks, before he also boarded. Six convicts were already seated at their oars, chatting amongst themselves and ignoring Theo and Franks. The boat’s coxswain sat at the stern, picking at some dirt under his fingernail.

As Theo stowed the supplies, two officers arrived and stepped onto the boat; the more senior-ranked, and older of the two, had his dark hair pulled back in a pony tail—his good looks marred by a pock-marked skin. The other was a young officer with brown wavy hair. Governor Phillip strode up with a third officer, who appeared to be in his late-thirties with a long thin face and a head topped with salt-and-pepper curly hair. The officers exchanged pleasantries amongst themselves and found their seats.

“Are the supplies I requested on board?” The governor directed his question to the privates.

“Yes sir,” Franks replied.

“Let’s get underway, shall we?”

At the coxswain’s instructions, the men found their oars, then dug them into the water, negotiating the boat away from the wharf.

As the rowboat pulled away, the governor took a flask from his pocket and took a drink. Recapping it, he said, “Captain Lieutenant Tench, perhaps you can give the others some background to our mission today.”

The officer with the pock-marked face turned so all the officers could hear him. “As I told Governor Phillip, Captain Nepean found Bennelong and Colebee at Manly Cove two days ago with a sizeable group of natives, hacking a dead whale to pieces for food.” He paused to settle in a more stable position as the boat lurched. “The natives asked for hatchets, but Nepean’s group could only give them a few things of little use. Before they left, Bennelong gave Nepean three or four great hunks of whale as a gift for the governor.”

“You all know of my desire to improve relations with the natives here,” the governor said. “Bennelong’s made the first move. This is an opportunity for us to show good will and further cement our relationship.”

“He appears to be in friendly spirits,” the officer with brown curly hair said. “I was with Captain Nepean’s group. Bennelong was larking about and kissed me!” Theo stifled a laugh. The man looked like he had just sucked a lemon.

“That must have been a surprise, Lieutenant Waterhouse,” the governor said, smirking. “These people can be hard to read. So I urge caution. We will need to assess the mood with care when we arrive, and I ask that you follow my lead.”

As they pulled further away from the port, the calmness of the water changed and the rowers had to pull harder to negotiate the swells of the harbour. From the journey’s outset, the comfort of land remained visible. The stunning coastline was rugged with tall cliffs and sandstone rocks, with the occasional white sandy beach fringed with bushland. Now, they had large tracts of water surrounding them on all sides. The crystal clear water turned now to a bruised purple, as the waves picked up.

“Sir, we are just coming past the heads, so I suggest you all hold on tighter,” said the officer with the curly salt-and-pepper hair. “The harbour can be rough between the south and north headlands.”

“Thank you, Collins,” the governor said.

Theo clamped his hat more firmly on his head and adjusted his hold on the musket. He braced his feet the best he could against the hull and gripped his seat with his free hand. His stomach rolled as the rowboat crested each wave. Briny air filled his nostrils as spray from the sea splashed his face with salt.

The group remained silent until they were past the heads, where the water calmed again as they continued northward toward Manly Cove. The rowers were tiring. Soon, a large expanse of sand appeared, punctuated in the middle with a black whale carcass, half submerged in the water. The shape grew larger as the boat approached. Surrounding the carcass and spread along the beach were at least one hundred natives.

“Sir, the wind is coming from the south-east, so I suggest that we put the boat in to the right of the carcass,” Lieutenant Waterhouse said.

“Coxswain?” the governor looked at the man managing the boat, who acknowledged the request with a nod.

“Privates, you and the rowers remain with the boat,” the governor said to Theo and Franks, as the boat slid up onto the sand, jolting everyone forward when the hull dug in.

The governor jumped over the side and strode off. His officers gathered the supplies and scrambled to follow. Groaning with relief, the oarsmen sat back in their seats and rubbed at blisters that were forming—their shirts glued to their backs with sweat.

As the governor and the officers approached the group, a chill ran up Theo’s spine as all of the natives stopped what they were doing to watch the white men approach.

“I’ve got to take a piss,” John Franks announced as he prepared to get off the boat.

“Franks!” Theo said, alarmed. “We were told to stay put.” It wasn’t ideal to be left alone to manage seven convicts, and what would happen if things turned ugly on the beach? If Franks left, Theo’s musket was their only means of defence.

“I won’t be a moment,” Franks said. He slipped over the side of the boat furthest from those on the beach and disappeared into the bush.

Things were happening now on the beach. The natives split into two groups and moved to the left and right of Phillip and his men, as if to surround them—they were vastly outnumbered. The sight of the dark-skinned men, many holding sticks or spears, made Theo’s palms sweat. How vulnerable we are!

Governor Phillip held his hand up, signalling to his party. He and the three officers stopped and retreated a few steps. This seemed to appease the natives as they reassembled back into a single group.

Theo let out a quiet breath. For those in the boat, their focus remained on the scene playing out on the beach. But Theo kept glancing into the bush wondering what was taking Franks so long? Whilst Theo was distracted, one of the older oarsmen took this moment as his opportunity to flee. Being farthest from Theo, he could not grab hold of the fleeing man before the he jumped over the boat’s edge and darted into the bush. Christ!

Theo raised his musket and aimed, but in a split second decided not to shoot the escaping convict, for fear of startling the natives. Where’s bloody Franks?!

Watching the back of the escaping convict, frustration burned in Theo’s chest. He had to stay in the boat to secure the remaining convicts.

“Anyone else have the same thought, I will not hesitate to shoot you” he said, lifting his musket. His scalp prickled. It was madness that a convict would choose to escape, and Theo didn’t like his survival chances, but still—it happened, and on Theo’s watch.

On the beach, the governor beckoned for Bennelong to come forward, and he did so holding a long wooden-barbed spear. The governor motioned to swap the spear for the supplies the officers were holding. Bennelong walked to the bush edge and put the spear down, replacing it for a stick, which he then presented to the governor. The native Colebee also came forward, and he helped Bennelong take the supplies from the officers.

Bennelong and Colebee appeared to chat in a friendly manner with the governor, who had stepped apart from the officers. Bennelong appeared to introduce different natives to the governor. The natives stood back in separate groups, many watchful. It seemed to be going well.

Theo jumped as Franks reappeared and climbed back into the boat with a smug grin, which faded when he saw Theo’s face and the missing oarsman.

“What happened?” he said.

“This is on you,” Theo said.

Bennelong pointed out a native to the governor’s right. Governor Phillip held out both his hands and called to him, then stepped towards the native, with David Collins close behind. Theo didn’t like the look of what was happening. The closer the governor approached, the more agitated the native appeared.

Collins said something to the governor. The governor reached under his jacket and withdrew a dagger from the sheath at his side and dropped it onto the sand.

But this had the opposite of the intended effect on the native man, who stepped back, eyes wide. In a swift motion, the native kicked Bennelong’s spear out from the grass. Both the governor and Collins stopped dead in their tracks—the governor held up his hands, and Theo’s breath caught in his throat.

Appealing to the man, the governor spoke a few words in a native language which floated back to the boat. In response, the native stepped one foot back and released his spear with such force that it pierced the governor’s right shoulder. The governor staggered back, Collins reaching to catch him.

Everyone on the boat inhaled with surprise. Theo’s mind whirled as his body went cold—they’d attacked the governor, what now?

“Get ready,” he instructed the rowers, who all scrambled for their oars.

As the governor collapsed to his knees, the native who threw the spear dashed into the bush. Bennelong and Colebee also fled, along with most others from the beach. As Collins rushed to the governor’s aid, several natives launched spears in the general confusion that followed, with none finding their mark. Tench and Waterhouse raced forward and helped Collins drag the wounded governor to safety, taking care to avoid the wooden barb of the spear piercing through his back. With every step, the governor screamed as the pole end of the spear hit the ground. Tench tried to steady it. Once out of reach of the natives’ spears, they laid the governor on his side. Captain Lieutenant Tench yelled at Theo and Franks to cover them. By this stage, Theo and Franks had jumped out of the boat, their muskets aimed just above the heads of the natives. Theo got a shot off. Franks’ musket jammed. The remaining natives scattered, emptying the beach save for the whale carcass, the wounded governor and the officers trying to save him.

Lieutenant Waterhouse knelt by the governor and attempted to break the spear’s pole, so they could move the governor into the boat. With each attempt the governor moaned, and it took several tries with much effort from Waterhouse before it snapped. Blood soaked the governor’s shirt, front and back, yet he remained conscious. They hoisted the white-faced governor back to his feet and loaded him onto the boat, laying him down. Theo and Franks pushed the boat off the sand, then jumped in once it floated.

Lieutenant Waterhouse noticed the missing oarsman. “Where is he?!”

Theo swallowed. “He escaped, sir.” Theo and Franks found their seats. The five oarsmen got ready to row.

“How?” Fury tinged Waterhouse’s words.

“With only one of us to guard the convicts, I couldn’t leave the boat to chase him, sir,” Theo said.

“And where were you, private?” Waterhouse rounded on Franks.

“I, er, well, I needed to relieve myself, sir. He had scarpered before I came back.”

“This is a shambles,” Collins said, taking off his jacket and folding it under the governor’s head. “We’ll be taking this up with your captain.”

Theo cringed inside. The one time Captain Hill trusted him with an important mission, not only was the governor injured, but a prisoner escaped!

“You private,” Waterhouse indicated to Franks, “take the sixth position on the oars. Let’s get back to Sydney Cove as quick as we can.”

Franks removed his jacket whilst giving Theo a thunderous look. He sat in the vacant seat and bent his back to pick up the oars.

The five mile trip back seemed twice as long as the trip over. The wind had picked up and the rowers struggled in the choppy water. Theo was anxious to be back at the wharf, for the governor to get medical aid. He glanced at the ashen face of the governor, who had not moved since the officers laid him down. Could he die? What would Captain Hill think of all this?

Back at Port Jackson, they lifted the governor out of the boat and the officers carried him to his home for treatment. Theo climbed out the boat and Franks followed, bumping his shoulder against Theo as he brushed past. “You dog, Feutrill,” he said. “I won’t forget this.”

*

Theo and Franks reported immediately to Captain Hill, whose face was pulled down as he received their report. He expressed his “abject dissatisfaction” with the acquittal of their duties, and “deep dismay” at the turn of events on the beach. He strode out to see to the governor’s health and learn first-hand what actually happened, leaving Theo and Franks behind in his tent, like naughty children.

News of the attack on the governor spread around the settlement, and the military issued instructions for all soldiers to be on high alert in the event of reprisals—from either the settlers or the natives—though the governor made it clear he did not wish for any retaliation.

Over the following week, Bennelong and Colebee, who were previously regular visitors—were not seen at the settlement. Ten days following the incident, during which the governor continued to heal, Theo was submitting his daily report when Llewellyn caught up with him in the soldier’s mess tent.

“Feutrill, you saw the governor speared, didn’t you?”

In the days since it happened, it was all anyone would talk about. What had Theo seen? What was his role? But for Theo, it was something he wanted to forget. He didn’t know at the time whether they’d all be attacked or how close he was to losing his life? Whether he’d have to shoot someone to save themselves? He just wanted it behind him now. The governor was on the mend, and the escaped convict eventually returned to the settlement, near starvation.

Llewellyn didn’t wait for Theo to answer. “Did you hear Bennelong and Colebee are back? Met with the governor today?”

Theo’s ears pricked up. “How’d that go?”

“From what I’ve heard, it was a man called Willemering who speared him. But the governor has accepted that he did so out of impulse and self-preservation. He wants no further animosity—from either side. I think they’ve agreed to a truce of sorts.”

Theo huffed out a breath. “I think that’s good news.”

Llewellyn saw another person he wanted to share the gossip with, so clapped Theo on the shoulder and raced to catch up with him.

Impulse and self-preservation? As Theo headed back to his tent, he mulled that over. Located near the settlement is a clearing where the Cammeraygal tribe gathered for their rituals, and they welcomed the settlers to watch proceedings. He recalled a gathering from last week where a Cammeraygal called Carradah was the centre of a ritual—he’d apparently stabbed another member of the tribe, but not killed him. Theo learned that the tribe demanded Carradah receive payback before his crime could be forgiven.

Over two brutal nights, Theo and others gathered to watch the ritual, as Carradah used his bark shield to defend himself from the spears being thrown. Eventually one found its mark, pinning his lower arm to his side. Bright crimson blood oozed from the wound. Despite the injury, Carradah continued to avoid the remaining spears until the tribesmen exhausted their supply.

Theo thought it would be over then, but men, women and children of the tribe rushed forward to pick up the broken bits of the spears to piece them together, before resuming the attack. Carradah found a second wind and was quick on his feet as his shield took on further spears. Then, a spear pierced Carradah’s thigh, and the man sank to his knees. A tribal elder stepped forward and made an announcement. The attack stopped and the natives retreated into the bush, leaving just the European settlers to watch as Carradah’s injuries were attended to by a young native woman. Once he was patched up, they left the clearing.

Theo saw that the spear used on the governor was Bennelong’s. He wondered then, could the spearing have been a ritual punishment for the governor capturing Bennelong and Colebee when the First Fleet arrived? From the outside, Bennelong and Colebee appeared to get along with the governor since they were no long captives, but did they need to give the governor payback, so that they could forgive him? Did they lure the governor to Manly Cove for that very purpose? Surely, the governor must be contemplating the same thing. Whatever it was, Theo hoped it was now over.

##

More Than I Ever Had is available in paperback or eBook format from Amazon (world-wide). Link to the book on the Australian site here.

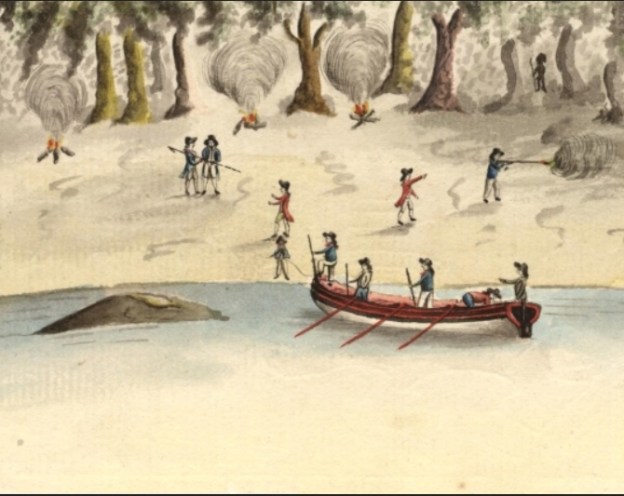

Main image:

From the collection of the Natural History Museum (UK). By a Port Jackson painter, ca. 1790.

The inscription reads:

‘The governor making the best of his way to the boat after being wounded with the spear sticking in his shoulder’